The

Boston Comic Con was this weekend, a convention just mainstream

enough that it can support that one vendor with twenty long boxes

full of crap no one outside of The Comics Journal has ever heard of,

and yet, not run him out of town for having a box labelled "Vintage

Playboys ½ off". It's a happy medium, that i don't see lasting

much longer. But, I'm not one to look a gift horse in the mouth,

so I picked up a stack of Taboo's along with a collection of Bilal

short stories, and a Manara book I've never heard of called

Gullivera.

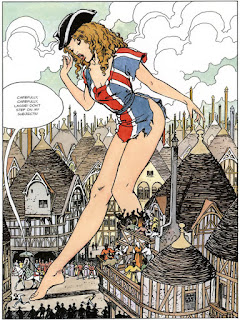

I've only had time to read Taboo #5 and Gullivera, so that's what I'll talk about. What's shocking about these two works is how they share an, almost identical story approach, yet, come at them from wildly different perspectives. Taboo #5 contains the first serialized chapter of Alan Moore's and Melinda Gebbie's Lost Girls, a (as Alan Moore describes it) pornographic re-imagining of Peter Pan, The Wizard of Oz, and Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, all set during the lead up to the first World War. Likewise Manra updates Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, injecting a skimpily dressed teenage girl traveling the high seas, in Gullivers stead.

The first things that jumps out when looking at both works is their use of children's books as a framing devices, this is reminiscent of comics first foray into pornography the Tijuana Bible, little eight page pamphlets featuring prominent comic strip characters in overtly sexual situations. This connection had to be on Moore's mind, since in addition to apeing the style, Lost Girls was serialized in eight page chunks, a direct riff on the format. Moore's use of children's characters, instead of comic characters (the modern equivalent of comic strip characters), is also interesting, it may simply be that these characters were in the public domain (as opposed to superhero’s who are held in perpetual copyright), but it's more likely that Moore used these characters to directly connect himself with "literature" and not "comics". Like he had previously done in League of Extraordinary Gentleman.

I've only had time to read Taboo #5 and Gullivera, so that's what I'll talk about. What's shocking about these two works is how they share an, almost identical story approach, yet, come at them from wildly different perspectives. Taboo #5 contains the first serialized chapter of Alan Moore's and Melinda Gebbie's Lost Girls, a (as Alan Moore describes it) pornographic re-imagining of Peter Pan, The Wizard of Oz, and Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, all set during the lead up to the first World War. Likewise Manra updates Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, injecting a skimpily dressed teenage girl traveling the high seas, in Gullivers stead.

The first things that jumps out when looking at both works is their use of children's books as a framing devices, this is reminiscent of comics first foray into pornography the Tijuana Bible, little eight page pamphlets featuring prominent comic strip characters in overtly sexual situations. This connection had to be on Moore's mind, since in addition to apeing the style, Lost Girls was serialized in eight page chunks, a direct riff on the format. Moore's use of children's characters, instead of comic characters (the modern equivalent of comic strip characters), is also interesting, it may simply be that these characters were in the public domain (as opposed to superhero’s who are held in perpetual copyright), but it's more likely that Moore used these characters to directly connect himself with "literature" and not "comics". Like he had previously done in League of Extraordinary Gentleman.

When read alongside one another, each author's approach to smut is made abundantly clear. Moore's Lost Girls may be paraded around as pornography, it does indeed depict explicit sexual encounters, more so than Manara's Gullivera, but it has the air of an essay throughout its pages. Moore's writing style, and knowledge of censorship laws, made Lost Girls into more of an academic critique than erotica. Putting its literary nature at the forefront, at the expense of its attempted-eroticism. In the introduction to Lost Girls Stephen Bissette informs the readers of the long history of censorship in the United States. American Literature, in stark contrast to that of the Orient and Europe (with the exception of the UK), has been puritanical in its approach to obscenity and perceived eroticism in art. These restraints held the genre in the literary backwater for centuries, lacking any significant works until the late 19th century. Which was went to prove the genre's distinct position as a non- literary to its detractors (Similar to comics need to "prove" themselves to academia with Maus / Watchmen / Acme Novelty before they could be affirmed as capital A- Art) The few books that did see publication, Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer in the 1930's, and William S. Burroughs Naked Lunch in the 1960's, each faced heavy censorship until they were deemed to have "distinct artistic value" to the community at large.

Lost

Girls

was

created in this vacuum; and it shows.

The first installment of Lost Girls is tame in comparison to what's to come. Instead of focusing on titulation, it focuses on reinforcing the idea of story. Alice is depicted (off panel) telling the fairy tale Humpty Dumpty to a prostitute, following the young girl plea's. This becomes a recurring theme throughout the book, as each character tells the others a story, first of their sexual awakening (most requiring a certain level of coercion to begin their tales) then later expanding on their various dalliances with perversion. This technique was first utalized in Marquis de Sade's 120 Days of Sodom (who shares a striking resemblance to Monsieur Rougeur, the hotel's owner), who centered his chapters around prostitute's telling the Libertines a story of depravity from their trade, these stories were later inflicted on the Libertines prisoners either thematically or literally. Moore, unlike Sade, who used sex as a force of degradation for his characters, uses sexuality to show the pinnacle of humanity, contrasting it with the horrors of war "I suppose that's what war destroys. All the art and architecture, the fields of flowers and young people's dreams...all the imagination". By framing his story, and the opening sequence, this way Moore uses accepted literature to circumvent any charges of obscenity, but fails to create the sense of eroticism the project was meant too.

The first installment of Lost Girls is tame in comparison to what's to come. Instead of focusing on titulation, it focuses on reinforcing the idea of story. Alice is depicted (off panel) telling the fairy tale Humpty Dumpty to a prostitute, following the young girl plea's. This becomes a recurring theme throughout the book, as each character tells the others a story, first of their sexual awakening (most requiring a certain level of coercion to begin their tales) then later expanding on their various dalliances with perversion. This technique was first utalized in Marquis de Sade's 120 Days of Sodom (who shares a striking resemblance to Monsieur Rougeur, the hotel's owner), who centered his chapters around prostitute's telling the Libertines a story of depravity from their trade, these stories were later inflicted on the Libertines prisoners either thematically or literally. Moore, unlike Sade, who used sex as a force of degradation for his characters, uses sexuality to show the pinnacle of humanity, contrasting it with the horrors of war "I suppose that's what war destroys. All the art and architecture, the fields of flowers and young people's dreams...all the imagination". By framing his story, and the opening sequence, this way Moore uses accepted literature to circumvent any charges of obscenity, but fails to create the sense of eroticism the project was meant too.

Alternatively

Manara, who resides in Italy, did not need to justify his work as a

form of literature to such an extent (although many critics have made the argument)

as Moore, because of the mediums acceptance. Gullivera,

in contrast to Lost

Girls,

is a work of pornography, not academia. There is no unified-critique

of life to be found in this work, its goal is simply to inject a barely

clothed female into Swift's narrative, and see how often Manara can

depict her in even less clothing.

That’s not to say there's nothing else to his work, Manara makes it a point to keep the adventure yarn going, and inject humor when appropriate. He's retelling the story of Gulliver's Travels which is an adventure story foremost, not a veiled porn parody, a fact not lost on Manara.The first two adventures, which make up the bulk of this book, involve Gullivera visiting an island of miniaturized people and then one setteled by giants. These opening scenes are decidedly the raunchiest, but Manara is able to render a cityscape like no other, along with a kinetic sword fight between Gullivera and a rat (which few could ever equal), allowing the reader to linger elsewhere if they so want. On her third adventure Gullivera visits the County of Houyhnhnms, a land inhabited by talking horses, Manara uses this adventure to lighten the mood (in anticipation of the next stories distinct "heaviness"), having Gullivera immediately run to her ship following the "advances" of the locals. Gullivera's last adventure, to the floating city of Laputa, is unique in the book, in that it functions as a critique of mans need to over-philosophize at the expense of living "Of course, There are [Men]! But at night, they're too busy gazing at the stars and during the day they're dead to the world...or discussing philosophy. Come on up!" Its hard to read this sequence and not think of Moore's Lost Girls.

Gullivera and Lost Girls show how two masters of the medium can approach erotica in completely different ways, due to their respective cultures view on sex and art. Moore takes a literary approach to skirt around the charges of obscenity he's likely to face (and still does), as he attempts to bring pornography to the forefront of genre comics "Certainly it seemed to us [Moore and Gebbie] that sex, as a genre, was woefully under-represented in literature. Every other field of human experience—even rarefied ones like detective, spaceman or cowboy—have got whole genres dedicated to them. Whereas the only genre in which sex can be discussed is a disreputable, seamy, under-the-counter genre with absolutely no standards: [the pornography industry]—which is a kind of Bollywood for hip, sleazy ugliness." Manara though, living in a country where sex, as a genre, is respected (to a greater extent), allows himself to playfully adapt his source material, without the fear of persecution or censure. Creating a true adaptation, with distinctly pornographic elements, a feat not common to the genre,.

That’s not to say there's nothing else to his work, Manara makes it a point to keep the adventure yarn going, and inject humor when appropriate. He's retelling the story of Gulliver's Travels which is an adventure story foremost, not a veiled porn parody, a fact not lost on Manara.The first two adventures, which make up the bulk of this book, involve Gullivera visiting an island of miniaturized people and then one setteled by giants. These opening scenes are decidedly the raunchiest, but Manara is able to render a cityscape like no other, along with a kinetic sword fight between Gullivera and a rat (which few could ever equal), allowing the reader to linger elsewhere if they so want. On her third adventure Gullivera visits the County of Houyhnhnms, a land inhabited by talking horses, Manara uses this adventure to lighten the mood (in anticipation of the next stories distinct "heaviness"), having Gullivera immediately run to her ship following the "advances" of the locals. Gullivera's last adventure, to the floating city of Laputa, is unique in the book, in that it functions as a critique of mans need to over-philosophize at the expense of living "Of course, There are [Men]! But at night, they're too busy gazing at the stars and during the day they're dead to the world...or discussing philosophy. Come on up!" Its hard to read this sequence and not think of Moore's Lost Girls.

Gullivera and Lost Girls show how two masters of the medium can approach erotica in completely different ways, due to their respective cultures view on sex and art. Moore takes a literary approach to skirt around the charges of obscenity he's likely to face (and still does), as he attempts to bring pornography to the forefront of genre comics "Certainly it seemed to us [Moore and Gebbie] that sex, as a genre, was woefully under-represented in literature. Every other field of human experience—even rarefied ones like detective, spaceman or cowboy—have got whole genres dedicated to them. Whereas the only genre in which sex can be discussed is a disreputable, seamy, under-the-counter genre with absolutely no standards: [the pornography industry]—which is a kind of Bollywood for hip, sleazy ugliness." Manara though, living in a country where sex, as a genre, is respected (to a greater extent), allows himself to playfully adapt his source material, without the fear of persecution or censure. Creating a true adaptation, with distinctly pornographic elements, a feat not common to the genre,.